“I do not know, men of Athens, how my accusers affected you; as for me,I was almost carried away in spite of myself, so persuasively did they speak.

And yet, hardly anything of what they said is true.”

I – Orientation: Why This Is Not a Defense of a Man

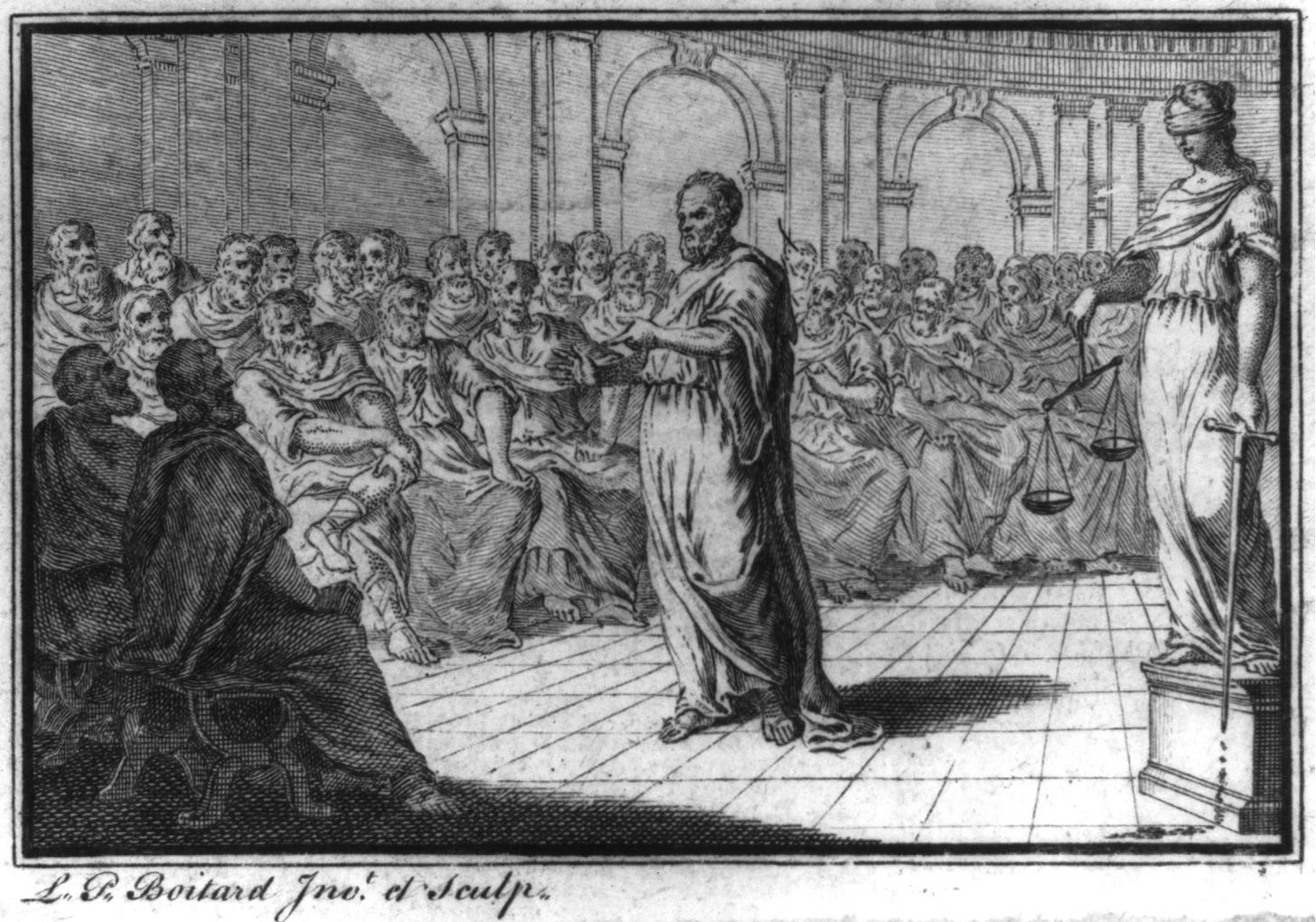

Standing before the Athenian jury, Plato recounts a most curious speech. Socrates offers his fellow citizens something quite bizarre. If this speech were merely an attempt to show innocence or secure mercy, Socrates fails quite miserably. Lest we take Socrates to be incompetent or absurd, he is doing something else entirely: rather than focusing primarily on innocence or guilt, Socrates publicly defends the practice of inquiry against those who wish to see it cease due to discomfort.

In doing so, Socrates reveals a remarkably minimal set of commitments. Namely, that the good consists primarily in attending to matters of the soul rather than matters of status or material benefit. Notice what he does not say: not “My teachings are true,” nor “My teachings are worthy of being allowed to continue.” Socrates makes the case for a way of relating to beliefs rather than settling which beliefs are right or wrong. In this sense, it is Athens on trial. The Athenians themselves must answer if they wish to put a man to death merely because he has destabilized those who think they know things. The Athens examined here is not necessarily the empirical city of history, but the civic and epistemic portrait constructed within Plato’s philosophical and dramatic presentation of the trial.

Elsewhere, I have suggested that inquiry often fails at two points. The first, and most important in the Apology, is that ignorance can be recognized. Following this, that aporia–a state of confusion that arises when one realizes he does not know what he thought he knew–is an intermediate state. Notice, crucially, how Socrates does not call those regarded as wise to be fools or evil for pretending to know when they do not, but merely that this type of self-deception is the very thing preventing them from being truly wise. Socrates even treats his primary accuser, Meletus, as a good and patriotic man. He only points out his inconsistency, not his motives or moral character.

This analysis does not ask whether Socrates was right or wrong, nor does it seek to answer if his defense was effective. What Socrates does do, much more interestingly, is test whether Athens could even recognize what “being right” could even mean. What follows, then, is not a defense against particular charges, but an exposure of how those charges could even be made at all. This reading does not deny any historical or forensic dimensions of the Apology. It does argue that Plato presents the trial as philosophical paradigm rather than a mere biography. This essay intentionally adopts a philosophically interpretative method over a philological one. It reads the Apology as a unified philosophical argument about inquiry, moral knowledge, and civic authority, rather than a historical reconstruction of Socrates’s trial or a determination of his legal guilt or innocence.

II – The Longstanding Accusation: Reputation Against Inquiry

Socrates opens with a distinction between two types of accusers. The first are those who have slandered him for many years, and the second are those like Meletus who bring up the current charges. Before addressing Meletus and his current accusers, he identifies his reputation as the true charge. This “slander”, according to Socrates, consists of the image painted of him over decades, reflected most famously in Aristophanes’s Clouds1. Aristophanes’s caricature is significant not because it appears to be accurate, but because it demonstrates how philosophical inquiry can be transformed into a theatrical stereotype that replaces argument with ridicule. This caricature cripples inquiry before it can begin.

He addresses his earlier slanderers as if they were present: that he is a natural philosopher, and a Sophist-for-hire. He denies this, and appeals to the jury themselves as witnesses against these activities. For inquiry to occur, the ground must be cleared of false impressions or motives. Could these charges even make sense without decades of falsehoods? By relying on reputation rather than dialectical engagement, philosophical discussion is reduced to moral suspicion.

Inquiry must also remain unpurchased. Otherwise, exploration of ideas hardens into reputation and profession. A Sophist who makes whatever argument he is paid to make is unable to analyze possible biases and presuppositions. He is bound to avoid such examination unless it serves the defeat of an opponent. Can inquiry be free where there is a material incentive to say certain questions are closed, or that specific answers are certain?

III – The Oracle: Wisdom as Freedom from Self-Deception

Socrates then appeals to Apollo’s oracle of Delphi.2 The oracle’s proclamation is treated as divine provocation rather than an acclamation. The man who claims to know nothing is proclaimed by Apollo to be the wisest among men. Socrates treats this as a challenge to find one wiser than him rather than resting on the title of “most wise”. This prompts him to find the men with the greatest reputation for wisdom, and he often finds they simply do not know what they are talking about. The oracle is honored by being treated as a provocation to test rather than a trophy to display. He comes to a simple conclusion: neither possesses the wisdom each presumes, but only one recognizes this lack. Socrates avoids self-deception through inquiry, while the “wise” continue to assert their wisdom that cannot withstand questioning.

Socrates’s piety is not in submission to a conclusion, but fidelity to inquiry itself: the god’s word is honored by being tested rather than merely repeated. His god calls him wise, yet he tests the oracle’s proclamation through inquiry. The more he questioned, the more he found that they stood in the same epistemic condition. He only remains the “wiser” through this negative wisdom.

Neither the wise men, nor the politicians, nor the poets, nor the craftsmen, could withstand his questioning. Only the humble laborer appears more likely to preserve the space in which inquiry can occur. To Socrates, the primary function of inquiry as not the proclamation of truth, but the avoidance of self-deception through which truth might become accessible.

The cost of this inquiry and resistance to self-deception is the burden of a poor reputation. To Socrates, human wisdom is worth very little, but honesty with the self is worth both living and dying for. The onlookers of the inquiry left assuming that Socrates was wise and the expert was not, missing the point of inquiry as a shared attempt at understanding rather than a contest of reputation and rhetorical ability.

It is against this background–where reputation replaces inquiry and authority collapses under examination–that Socrates then turns to Meletus not merely as an accuser, but as a living demonstration of a failure of inquiry.

IV – Elenchus In Action: Self-Deception Exposed

If Socrates’s earlier reflections expose the cultural and epistemic conditions that made this trial possible, the exchange with Meletus demonstrates those conditions in action. Meletus is not merely an accuser bringing charges. Through Socrates’s elenchus, he becomes an illustration of what occurs when accusation and moral certainty replace shared inquiry.

Socrates, before naming the charges, acknowledges Meletus as both a good and patriotic man. He does not approach Meletus as an enemy to be defeated, but as an equal interlocutor with claims to be mutually examined. For inquiry to occur, Socrates cuts off the possibility of dismissal based on motives. He addresses the charges themselves rather than Meletus’s character.

Meletus’s first charge collapses under questioning. Meletus universalizes the good of the men of Athens and contrasts this with Socrates, supposedly the sole corrupter of youth in the city. Meletus claims that all Athenians improve the youth, while Socrates alone corrupts them. Socrates exposes the implausibility of this by comparing moral education to horse training: improvement typically requires specialized knowledge rather than universal competence. Meletus inadvertently asserts that moral expertise is both universal and effortless, while corruption is singular and exceptional. The analogy reveals not only a contradiction, but a deeper assumption about moral knowledge that Meletus never examines or articulates.

Socrates then secures Meletus’s agreement that no man willingly seeks harm. Why would Socrates cause those closest to him to become corrupt? If Socrates intentionally corrupts those around him, he would risk harm from those whom he has corrupted, making intentional corruption irrational. By Meletus’s own admission, Socrates is either innocent of corrupting the youth, or he only does so unintentionally. If the corruption is unintentional, no one has attempted to correct him prior to this trial. If Meletus aimed to prevent the corruption of the Athenian youth, the right thing to do would be to correct, rather than punish. Punishment presupposes moral knowledge that Meletus fails to articulate.

This moment reveals a deeper failure of inquiry: the refusal to acknowledge that ignorance can be recognized. If Meletus truly believed Socrates corrupted the youth, the reasonable course of action would be correction prior to punishment. Inquiry presupposes the possibility that one’s own understanding may be incomplete. By moving directly to accusation and penalty, Meletus treats his moral judgment as settled before it has been examined. The trial becomes an assertion of certainty and not a search for clarity.

A second breakdown appears in the form of contradiction. Socrates is accused both of atheism and of introducing new divinities. These charges cannot coexist. The accusation does not merely collapse logically; it demonstrates how rhetoric assembled from suspicion can replace conceptual coherence. The contradiction exposes a willingness to punish before clarifying what exactly is being alleged.

A third failure is the absence of the mutual clarity required for inquiry. Meletus accuses Socrates of teaching doctrines associated with Anaxagoras. Even when corrected, Meletus persists in making the claim. Error alone does not destroy inquiry, but refusal of correction does. Inquiry requires participants capable of revising their claims when contradictions emerge or correction is made in good faith. Meletus’s persistence reveals not intellectual defeat, but epistemic closure in the face of correction. These failures are not isolated logical errors but form a pattern: accusation replaces inquiry when certainty is treated as prior to understanding.

Meletus is neither foolish nor malicious in the text. Even Socrates recognizes his sincerity. Meletus, however, is epistemically unprepared to defend his own accusations. Can a society punish what it cannot define? Can one be held to account for a definition of “corruption” that cannot be articulated by the accuser? The failure of Meletus is not the failure of an individual accuser, but the exposure of a civic condition in which moral judgment precedes understanding.

Socrates has shown, through Meletus’s failure to create a space where inquiry can occur, that the real charge is not against any particular belief but a way of relating to beliefs: one that treats certainty as prior to examination. The trial is not about what teachings are right or wrong, but about whether Athens can even tolerate a man who refuses to settle questions in advance. That refusal now moves from the examination of Meletus to the examination of Athens itself.

V – Sentencing: Civic Norms Exposed By Inquiry

Socrates makes for a rather bizarre defendant. Even he recognizes that, while he believes his argument is sound, persuasion will be difficult. He does not appeal to pity, as a husband and father, nor to outrage, nor to submission, nor to negotiation for survival. He is neither angry nor resentful, and is surprised that the vote is so close. Where most defendants would plead under the threat of Meletus’s request for the death penalty, Socrates continues performing inquiry. Socrates treats the verdict as data about civic judgment rather than a personal tragedy.

When asked to propose an alternative punishment, he is in quite the conundrum. As he mentioned earlier, should a man willingly wish harm to come upon himself? If the penalty fits what a man deserves, what does Socrates deserve given his commitment to the claim that he has cleared himself of the charges at hand? In a move that seems arrogant, he gives what is, within his commitments, the only logically consistent proposal: to be rewarded. Socrates requests meals in the Prytaneum, a place where athletes and foreign diplomats are honored. He views himself as a poor benefactor, offering a counter-assessment at the cost of provoking the jury.

Is this arrogance? Satire? Irony? To remain consistent with his earlier commitments, it cannot be any of those. It is a reductio ad absurdum of Athenian moral evaluation. If Olympic victors and diplomats receive honor for making Athens happy, does not Socrates deserve the same honor for attempting to improve the souls of the city’s citizenry? Perhaps an even greater honor? This is rhetorically ineffective within conventional expectations of defense, but the only position consistent with Socrates’s earlier commitments. It is as if he asks Athens: “Is civic excellence measured by pleasure, prestige, or by moral improvement?” Is the city to be one built upon a culture of honor, or a culture of ethics? For Socrates’s counter-assessment to make sense, he must be committed to moral improvement as a civic good, rather than an accident of mere rule-following.

Socrates also demonstrates remarkable consistency in his ethical commitments. If no man should willingly wish harm upon himself, he must refuse to propose punishment he does not deserve. He refuses to propose exile, which would simply lead to him being run out of another city in his old age. He refuses imprisonment, because he maintains that he has committed no wrongdoing. He also refuses to propose silence, as he views silence as disobedience to the divine mandate he attributes to Apollo. This would be a direct violation of the divine provocation mentioned earlier.

Socrates does admit: he does not feel he deserves a punishment. If one is offered, his friends will pay a considerable fine on his behalf. This is offered as a final concession. The result is revealing: more jurors vote for death than had voted for guilt. The attempt to measure Socrates by civic norms exposes how deeply those norms resist philosophical scrutiny.

VI – Aftermath: Judgement Against Inquiry

After receiving the death penalty, Socrates contrasts his defense with what was expected of him: pleading, pity, and persuasion. And for what reason does Socrates do this, in the face of death? He states plainly that he would rather die than live after making a shameful defense. To Socrates, there is no value in avoiding death. Does a soldier lay down his arms and plead with his enemy? Socrates’s enemy is not death, but wickedness. Inquiry does not give Socrates invulnerability; fidelity to justice does. Inquiry merely keeps him from betraying what justice could even be.

Wickedness “runs faster than death” and lays hold of those who fear death more than dishonor and immorality. Socrates offers Athens a prophecy–albeit a more pragmatic than religious one–that vengeance will come upon the city that will be much harder to bear than mere death. The vengeance is that Athens will remain unexamined, and that inquiry will continue.

This re-framing of the fear of death as worse than self-deception is not mere courage, but calls into question if the fear of death is even valid. To Socrates, the fear of death only works if we pretend to know something one cannot know, which is what comes afterwards. People fear death because they assume it is bad, but how do they know such a thing?

Why should one deceive himself into thinking death is something worth being afraid of? Death could easily be perpetual nothingness, or even a blessing. What grounds that it is an evil thing to be avoided? If there is nothing, then a man may rest after a life of cares, temptations, and injuries. If it is a blessing, and a transfer from one place to another, there is a chance he can continue to inquire with the great men of legend and renown. In either case, it cannot rationally justify injustice. Athens offers no answer. Rather than calling these men cowards, he transforms his situation into a problem of claims about knowledge.

This reveals some of Socrates’s deep philosophical commitments. To Socrates, for this move to make any sense, moral wrongdoing must be worse than physical harm. Ignorance must be something dangerous when mistaken for knowledge. Based on this, Socrates must refuse to act on false certainty, because false certainty, when used as power over others, becomes injustice.

Many would believe, like Athens, that death is the ultimate punishment and that survival is the highest rational priority. To Socrates, the jury is operating from a place of opinion masquerading as knowledge. How can men judge life and death, when they do not even know what death is? Athens puts a man to death for the sake of avoiding giving an account of their conduct and knowledge, and in the end, only creates the conditions for those to come later and demand such an account. If Socrates rejects fear of death as false knowledge, how does he determine which action is right and wrong without certainty?

Socrates speaks of his daimonion, his “familiar prophetic power”, as constraint on his action.3 This daimonion does not act as a vehicle for divine positive doctrine, but only to prevent and oppose. It does not prohibit him from delivering his defense and from accepting the consequences knowing what is at stake. Even Socrates does not claim what this silence means, but views it as hopeful evidence rather than proof. This experiential treatment allows the daimonion to function as a constraint on Socrates’s moral reasoning. At the same time, it preserves its religious significance within Athenian piety rather than reducing it to psychological metaphor.

Socrates does not claim to know the good in advance, but that he can sometimes recognize when he is moving towards error. To him, inquiry is not about possession of truth or the accumulation of knowledge, but the avoidance of error. Divine authority is often thought of as acting through signs, omens, commands, spectacle, and proclamations. How novel is this in a society where religion is used as social cohesion, it is placed against an internal ethical discipline.

Socrates then asserts that a good man cannot be harmed in life or in death.4 He re-defines harm as moral corruption, not physical suffering or death. For this to make any sense, Socrates must believe that the soul is morally primary above the physical, and that external events cannot corrupt virtue. By this reasoning, injustice becomes a wound the wrongdoer inflicts upon himself. Inquiry into justice allows the just man to endure injustice, not because injustice ceases to be evil, but because wrongdoing corrupts the soul of the one who commits it, while external suffering cannot corrupt the soul of the one who remains just. If, within Socrates’s moral framework, a good man cannot be harmed even by death, then the trial no longer judges Socrates but instead reveals what Athens must already believe harm and justice to be.

To many, punishment is harm and death is the ultimate version of harm. To Socrates, the true harm is the risk that the jury has opened itself to: harm to themselves through injustice. The jury thinks they can control Socrates’s fate, while Socrates implies that Athens has done no more than determine its own moral decay.

His “pragmatic” prophecy does little divine work, but rather names the necessity of examination. Rather than calling down divine punishment for injustice, he names something inevitable about human nature when opinion is mistaken for wisdom. The act of suppressing inquiry is what often leads to the multiplication of it. Socrates is the symptom of inquiry and not its origin. If Athens believes that killing this man removes instability, Socrates implies that suppressing examination increases the very resentment and rebellion that leads to its proliferation. Socrates’s questioning is a cooperative exposure of ignorance, when many philosophical traditions who came after him made use of inquiry as an adversarial exposure of authority.

The final reversal of this speech is that Athens attempts to judge Socrates’s beliefs, but Socrates exposes the city’s inability to judge knowledge itself. This work cannot be done through an emotional appeal, as such a thing validates what Athens expects from a courtroom “performance”. He maintains his integrity and adherence to inquiry as a confrontation of the civic body itself.

To Socrates, justice cannot be mere legality. He shows that inquiry can shield the city from self-deception, steadies the individual against fear, and cannot be killed because it arises from eros for truth and the recognition of ignorance itself. The jury show themselves to be unable to distinguish between authority and understanding. Authority may be exercised, but only understanding frees a man from fear of death itself.

VII – Inquiry As A Life Practice: The Defense of a Way of Living

Socrates presents that inquiry is not the application of positive doctrine, but a posture towards existence. The trial shows what happens when a society rejects this posture. Inquiry must be something greater than a mere school of thought to risk reputation, comfort, social cohesion, and inner composure. This inquiry, to Socrates, does not arise from mere skepticism, but the marriage of eros for truth and recognition of ignorance. This eros is not only worth dying for, but worth reshaping the entire way a man lives. Inquiry emerges in the Apology as the governing orientation of Socratic philosophy.

Athens hardened its laws into dogma, and judged Socrates. Athens now stands before memory as an example rather than as a defendant. If Athens could not answer, will you? You and I are the inheritors of Socrates’s questioning and Athens’s verdict. Inquiry has shown itself to be unavoidable for those who refuse self-deception. It is not comfortable, heroic, or safe. Inquiry is tragic, but necessary.

We often feel certain questions are closed, and their answers presupposed. What licenses us to stop? Ignorance persists even when recognized, and often reappears clothed in sophistication. Inquiry, by leaving questions open, becomes the condition under which anything may count as truth. The enemy of inquiry is the treating of questions as closed – whether through their flattening into mere opinion, or hardening into dogma. Will you issue the verdict on yourself by putting your own internal Socrates to death?

The question is no longer “Was Socrates right?”, but “Will you live examined, or not?” The question returns to us. If his speech was not a defense of Socrates, it was a defense of the life he refused to abandon. Socrates was not acquitted or condemned – he was handed down to us.

We stand not before the Athenian jury, but the tribunal of time. Socrates’s speech no longer appears bizarre, but clarifying. If this speech once seemed to be a failure to secure innocence or obtain mercy, it now shows success in revealing what those things could never secure. Lest we take Athens to have judged a man, the speech instead shows that a city, and perhaps every reader after it, is placed under examination. What appeared to be a defense of a man proves to be a defense of inquiry itself – not as a doctrine to be learned, but as a way of living that refuses to abandon care of the soul, even when that refusal demands everything. Such discipline is required if one is to ask what truth demands of a life – and whether one is willing to pay its cost.

Socrates left us not with a set of doctrine, nor a school, but a measure by which life may be judged:

“On the other hand, if I say that it is the greatest good for a man to discuss virtue every day and those other things about which you hear me conversing and testing myself and others,for the unexamined life is not worth living for men,you will believe me even less”

Aristophanes, Clouds, lines 218-235.

Plato, Apology 20e-23c.

Apology 31c-d, 40a-c.

Apology 41c-d.

This is the first in a series of disciplined readings and analysis of Plato’s dialogues conducted under strict methodological constraints. Each analysis emphasizes fidelity to the text, exposure of assumptions, and genuine aporia. Two upocoming works are Interlude II: The Other Apology – Xenophon’s Account of the Trial of Socrates: A Rather Different View of the Same Man and Dialogue Analysis II: Euthyphro – A Comedy of (Category) Errors: Category Errors, Bad Definitions, and You. What’s Plato Really Doing in Euthyphro?